Three Ways the Ford Trimotor Revolutionized Air Travel

The Ford Motor Company is an American institution that traces its history back to the massive industrialization of the United States in the 19th century. Even the name ‘Ford’ is a household name globally, not just in the United States.

The company powered American industry into the 20th century with its new manufacturing techniques, most notably the assembly line concept, and it continues to be one of the largest automobile manufacturers almost 125 years after its inception.

While many undoubtedly recognize the Ford emblem and the vehicles it adorns, Ford manufactured another machine that few may recognize today, but which revolutionized the 1920s and 1930s. It was a flying machine called the Trimotor.

To understand why it was such an essential building block of modern commercial aviation, here are three ways the Ford Trimotor revolutionized an entire industry.

1. The Ford Trimotor was the first all-metal airliner

Early airplane designs were typically of either wood or steel structure with fabric skin, giving rise to the phrase “tube-and-fabric.” Due to this design concept, it was a major challenge to build an airplane large enough to carry more than a few passengers in modest comfort while maintaining an acceptable degree of structural soundness and reliability.

The most successful contender at the time was the Fokker F.VII, but its production ran short due to a series of accidents revealing a weakness in its design, which featured fabric skin on the fuselage (main body) and wings covered in plywood laminate.

Originally designed by William Bushnell Stout and his Stout Metal Airplane Company, the Ford Trimotor was the first airliner to introduce a metal frame in conjunction with aluminum alloy skin across the entire structure. The aluminum skin was corrugated, which added incredible strength to the lightweight metal. This made the airplane markedly more durable and rugged, giving passengers a heightened sense of safety.

One issue with the corrugated skin was its dramatically increased air resistance, known as ‘drag.’ This was easily overcome by the three powerful radial engines, giving rise to the name “Trimotor.”

2. The Ford Trimotor was more easily maintainable

As with most complex machines, airplanes require extensive maintenance. Complicated maintenance processes result in airplanes being grounded for longer periods of time and, therefore, not earning revenue.

The Trimotor was designed specifically to minimize maintenance intrusions on the schedule in two significant ways: first, the various cables, pulleys, and bell cranks that make up the airplane’s control system run externally along the body of the aircraft, where they can be noninvasively accessed.

Secondly, many of the passenger cabin appointments reflected those of a passenger railcar. Sharing components with other mass-produced equipment meant greater parts availability. On certain Trimotors, even the pilots’ control wheels were the same as the steering wheel on a Ford Model A.

3. The Trimotor made passenger air route networks practical

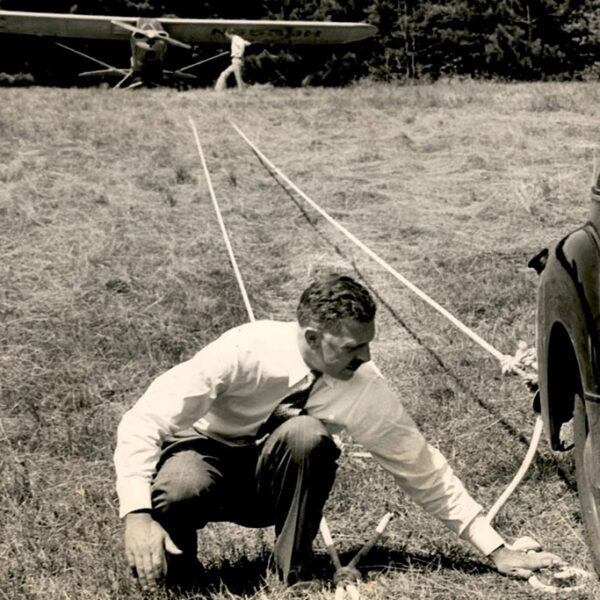

Just before the Trimotor’s introduction in 1926, passenger air travel was experiencing a very lackluster infancy. In fact, many airplane passengers of the day were merely tag-alongs on airmail and freight planes. Should there not be sufficient space or payload available, passengers would even be removed so that mail and freight could be carried.

Those who did fly often found themselves in noisy, cramped compartments and even exposed to the elements of wind, rain, and biting cold. But for a pair of coveralls, should they be so fortunate, they also found themselves covered in oil, fuel, or soot from engine exhaust.

The Trimotor avoided those problems by having an increased carrying capacity and designated cargo holds separate from the passenger cabin. This made passenger travel itself an enterprise for profit in the airline business.

Soon, airlines would develop route networks that spanned continents. The most notable of the day was a service called Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT), inaugurated in 1929. It transported passengers from New York City to Glendale, California, through a combination of night trains and daytime Trimotor flights. The TAT reduced the coast-to-coast travel time from 4 days via train to a mere 48 hours by train-plane combination.

The Trimotor truly gave birth to modern air travel. Virtually every airline in existence today can trace its routes to this fascinating machine. The revolutionary ideas that its 1920s designers poured into the airplane, along with the wisdom of early investors such as Henry and Edsel Ford, gave the Trimotor a lasting place in the annals of aviation. Ask virtually any Trimotor pilot, and they will describe the airplane as well-designed, relatively inexpensive, and, compared to other aircraft of the era, quite reliable.

Moreover, people can still find opportunities to fly on authentic Ford Trimotors today, a full century after it was initially designed. Nearly a dozen of the 199 aircraft built are still in good condition. Some even travel the country, giving rides to the public and winging modern travelers back to the golden age of flight.