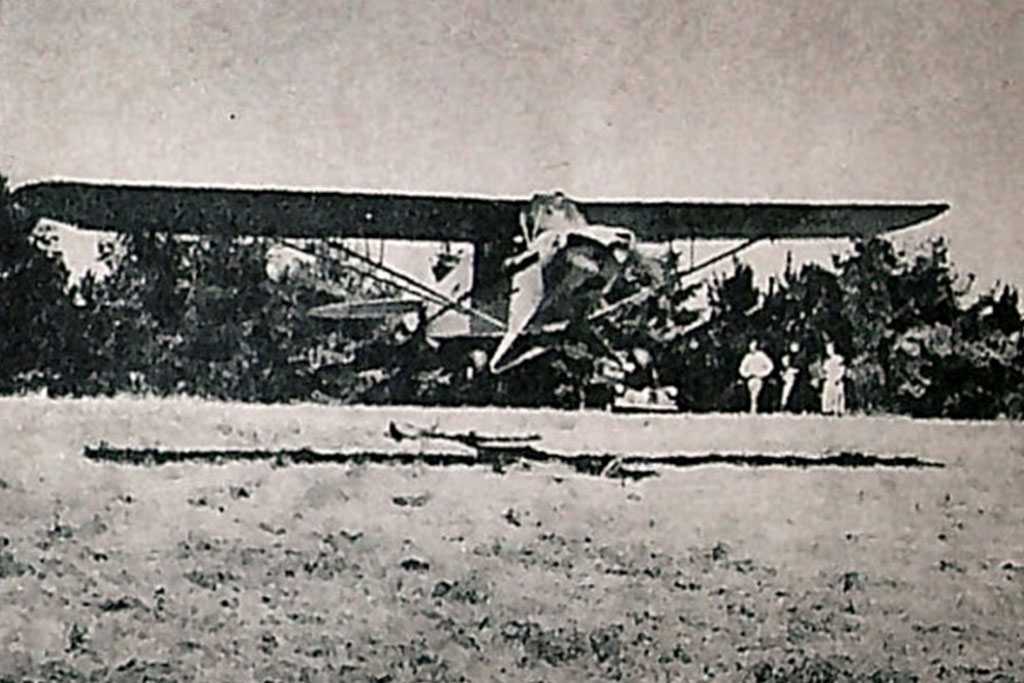

Piper Cub Catapult Takeoff

Historically, the convergence of annoyance and creativity has led to some of the world’s most innovative solutions, even in aviation. Such was the case in New York State during the late 1940s, when a pilot named Alfred B. Bennett became frustrated with his daily commute.

The commute wasn’t a long one. It was only about twenty miles, and it only took about thirty minutes. But as a pilot who worked in aircraft sales, Alfred knew that the commute would take only about eight to ten minutes by airplane – and because he was constantly flying at work, anyway, flying seemed like the obvious solution.

There was only one problem. Although he had a large backyard that was slightly larger than two acres, there was no room for a traditional runway. Besides being too short for most aircraft, it was surrounded by tall trees that would make takeoffs particularly challenging. Additionally, his land wasn’t level. The longest stretch was rolling, with several humps along its length.

But Alfred was both annoyed and creative, and one day, while observing his young son playing with a slingshot and shooting at various targets in the yard, inspiration struck.

Alfred owned an airplane that was nearly capable of operating out of his property. A simple, lightweight, and robust Piper Cub Special, it could easily negotiate rough, rolling terrain. It was even capable of landing in extremely short distances. But despite having a 90-horsepower engine that was more powerful than traditional Piper Cubs, clearing the trees at the departure end still required more runway than he had available.

What the Cub needed was more thrust. This would boost acceleration, enabling him to reach flying speed more quickly and providing the necessary energy to clear the trees.

As he watched his son playing with the slingshot, he wondered whether he could use a giant rubber band to launch his airplane into the sky. It was simple in theory. But could he do it in practice?

It didn’t take him long to determine that he could.

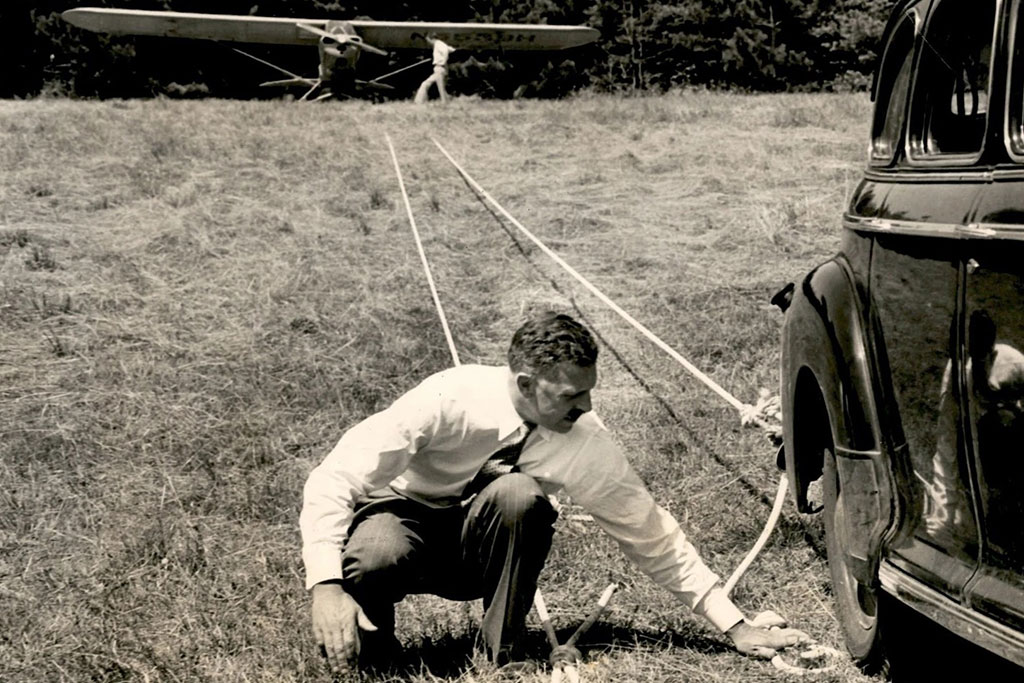

Alfred obtained two 90-foot elastic cords, two large stakes, and some hardware to fabricate a quick-release mechanism for his landing gear. Before long, he and his family developed a process that would enable slingshot takeoffs from his clearing in the woods.

Landing there wasn’t a problem. Alfred was able to make his approach at relatively slow speeds, made even slower with a slight headwind. After clearing the trees, he deftly performed a slip to drop into the clearing. As he rounded out to land, he was only traveling at about 35-40 miles per hour over the ground, and he brought the Cub to a stop with ease.

He then positioned the Cub for takeoff, shut down the engine, and prepared for the launch.

After securely blocking the main wheels into place with custom, long-handled chocks to prevent the plane from rolling forward, he attached the first elastic cord to his main landing gear and had his wife use the family car to pull it taut. She pulled it to twice its length – 180 feet – where they had driven anchors into the ground and attached it to one of them. She then repeated the process with the second elastic cord.

With each cord applying 450 pounds of force to the airplane, Alfred now had the energy necessary to accelerate to takeoff speed in time to clear the trees at the other end of the clearing.

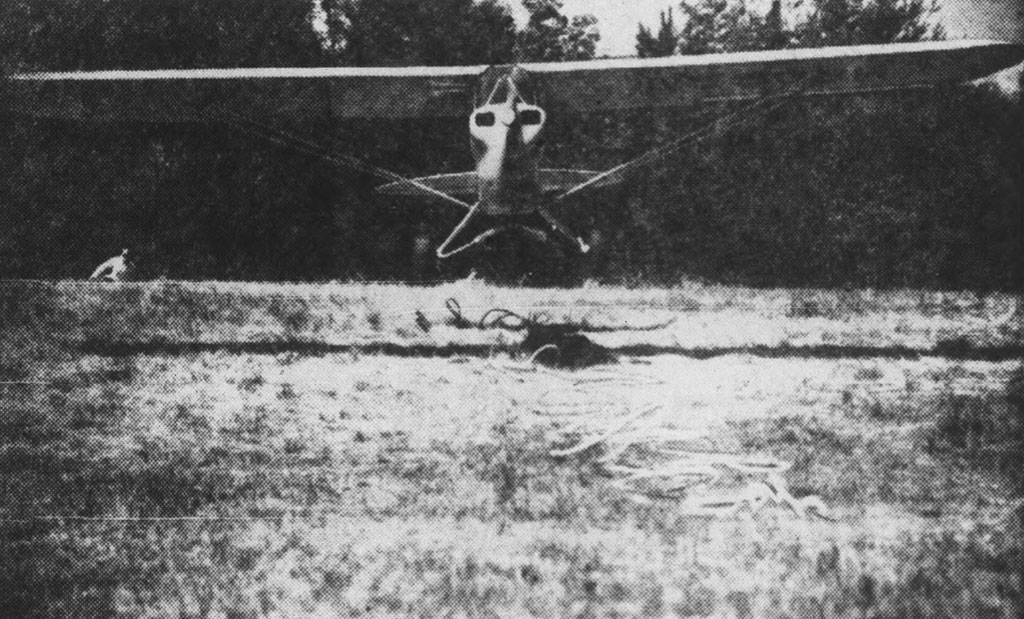

He strapped himself into the plane, started the engine, and after some pre-takeoff checks, applied full throttle. As the plane was trembling against the chocks, Alfred’s son and daughter pulled them free, and the launch began.

According to the Cub’s performance figures, it required some 350 feet to get off the ground when loaded to maximum takeoff weight. With partial fuel, one passenger, and a slight headwind, the ground roll decreases to roughly 250-300 feet. But using the catapult system, Alfred got off the ground in slightly more than 60 feet, at which point, the elastic cords fell free.

Subsequent takeoffs demonstrated a 90-foot ground roll with a second passenger aboard.

Getting off the ground, however, is only half the challenge. There were still trees to clear.

Alfred hugged the rolling ground, keeping the airplane just a few feet over the grass and utilizing “ground effect” – a zone of reduced drag that exists just over the surface. Building speed and energy, he waited until just before the trees before pitching up into a steep climb. This enabled him to clear the trees with ease, after which he leveled off and flew normally.

With his newfound capability and the efforts of his dedicated ground crew, Alfred commuted to work by airplane every day for two months in this manner. While the preflight procedures and takeoff process likely negated much of the 20 minutes saved by flying, Alfred undoubtedly enjoyed his commutes aloft far more than driving.

A true salesman, Alfred later presented the idea to various branches of the military, touting the capability to launch medevac flights from otherwise unusable areas. But, while he claimed that both the US Air Force and Army had expressed interest, the concept failed to take off as effectively as the airplanes it launched, and it ultimately became an obscure footnote in aviation history.